This magnificent Romanesque Christ, dated to the beginning of the first third of the 13th century, is housed in the so-called Museum of the Middle Ages (Musée du Moyen Âge) or Cluny in Paris. Although the museum doesn't have a website or mention it, nor does it have a wealth of information on the premises, there is information available online (FR):

Originating (with doubts) from the former headquarters of the Knights of Saint John of Jerusalem in Puy, it was acquired by Edmont Bresset, then an antique dealer in Marseille around 1955. In 1991, it passed to the Museum as inheritance tax.

It is undoubtedly one of the most famous pieces of Romanesque sculpture and also one of the most complex. It is composed of four distinct wooden elements: the body, the arms, and the head. Three of these pieces are carved from poplar wood, while the right arm was carved from oak—evidence of its subsequent restoration. Studies carried out by the Research Laboratory of the Museums of France and by Dominique Faunières at the time of its entry into the collections, and then by Dominique Bisel during the restoration of the work, have revealed other alterations. The polychromy was composed of several interposed layers, up to the level of the perizonium1. Aside from an ochre layer found throughout (corresponding to the seventh layer of the perizonium), these layers were also highly diverse depending on the location. At a fairly early date—because we find traces of it in the deepest layers of the polychrome, but not in the most superficial—part of the work's model was modified: it affected the left side of the head, including the ear and beard, and part of the right side of the thorax, resulting in the disappearance of certain layers. As for the nose, this is a recent restoration, as was the plate that closes the back to hide the interior hollow that replaced an older closure system. More curiously, the garment used to assemble the left arm has two angles: one that allows it to be placed horizontally, following the line of the shoulders; while the other angles the arm upward, the position it currently holds. It has not been possible to determine whether this is a restoration carried out on the occasion of the placement of the new arm or whether we are dealing with an interesting example of Christ in a position that could have been modified according to the development of the Easter cycle.

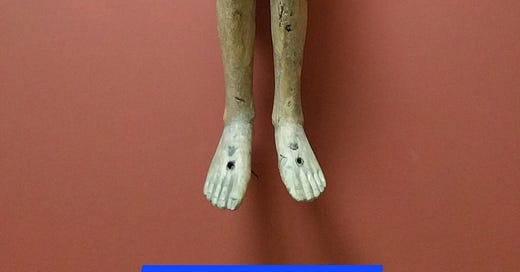

Christ's hair is long, styled in fairly straight strands, partly extending from the circular arc and parting from a central part before descending in a straight line to the nape of the neck and extending to the shoulders in three strands arranged in a fan-like fashion. The beard is made up of short strands at the temples, which lengthen as they move toward the chin, where they form spiral curls. The moustache, on the other hand, is made up of four strands that begin below the nose and fall slightly beyond the corners of the lips. The ears are large and clearly exposed. The head appears to be very tilted, although this impression must be highly qualified: if it falls forward, it only forms an angle of about 30° with respect to the vertical determined by the body. The extremely upright position of the arms, and in particular of the reconstructed right arm, is largely responsible for this impression of a head completely tilted toward the shoulder. The left arm, which is more firmly positioned, is at a much slighter angle to the perpendicular. The reshaped chest is smooth on the right side and clearly outlines the ribs on the left side. The moustache, on the other hand, is made up of four strands that begin below the nose and fall slightly beyond the corners of the lips. The ears are large and clearly exposed. The head appears to be very tilted, although this impression must be highly qualified: if it falls forward, it only forms an angle of about 30° to the vertical determined by the body. The extremely upright position of the arms, and in particular of the reshaped right arm, is largely responsible for this sensation of a head completely tilted toward the shoulder. The left arm, which is more firmly positioned, is at a much slighter angle to the perpendicular. The reshaped chest is smooth on the right side and clearly outlines the ribs on the left side. Narrower on the right than on the left, the abdomen is loose at the navel and falls over the perizonium girdle, thus highlighting one of the marks of Christ's humanity. The perizonium envelops the body from the hips, whose upper roundness stands out, to the lower thighs, freeing the kneecaps. Symmetrically worked, it is marked by elliptical folds, widely separated. The belt, which also has fairly loose folds, forms a circular knot before falling relatively straight between the thighs. The legs are clearly separated, as are the feet, which form an angle of just over 45° with the body, which seems to indicate that they were resting on a support and not nailed directly to the cross.

This Christ belongs to a well-defined production, of which relatively many examples have survived, especially considering the fragility of the wooden support. Most, if not all, of them are preserved in or originate from communes in the Upper Loire. It is rather tempting to think that these Christs, although not necessarily linked to the same workshop, are all derived from a common model and probably date from the last third of the 12th century. Despite its numerous repairs and restorations, the Christ in the museum is one of the best examples of this production, with which we can probably only compare the very similar head preserved in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

On the other hand, its origin remains unclear. It was purchased by the antiquarian Bresset from an abbot Dumas, manager of the Chadenac summer camp, who sold it on behalf of the Association of Catholic Summer Camps of the Upper Loire. The latter had received it as a legacy from Abbé Pascal, who is said to have found it in the commandery of the Hospitallers of Saint-Jean-de-Jérusalem in Le Puy-en-Velay. This commandery, whose first mention dates back to 1153 and whose oldest parts seem to have been built in the second half of the 12th century, has been the subject of several pastoral visits, notably in 1616 and 1789. Unfortunately, none of the minutes of these visits, although they are usually very precise regarding the furnishings, mention a Crucifixion. Under these conditions, one might wonder whether the museum's Christ was already present in the commandery before the Revolution or whether it only entered it during the major movements of works that marked the 19th century.

Originally published in Spanish both in Wordpress and in Substack.

Buy me a coffee. ☕️

The 1st third? I read that date 4 times & it sunk in. Omgosh this is magnificent. And it still exists. 🤯